A rich combination of poetry and musicianship can make the Ghazal a highly evolved and unique art.

The Ghazal as a poetic form originated in Persia in the tenth century. Though Persian in origin, the Indian ghazal has a distinctive character of its own, rooted in the Indian ethos. Its poetry is written in Urdu, a camp language born in India. Urdu is a Turkish word, meaning `bazaar for soldiers’. The base of the Urdu language is Indic; its vocabulary is a mixture of Hindi, Turkish; Arabic, and Persian. Urdu emerged when early Muslim dynasties ruled in India, and crystallized during the Mughal period. In its formative stages, Urdu was called Hindvi or Rekhta. The first evidential ghazal was written by Amir Khusro in the thirteenth century. This ghazal combines two cultures clothed in two languages – half of each line is in Persian, and the other half is in Brij-bhasha; and each couplet is arranged thus. Urdu had not till then consolidated .Along with the political regime, it shifted to the Deccan , and later moved up North again, where it became a sophisticated and elegant court language. The Urdu ghazal matured and attained its apex during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when it flourished in Delhi and Lucknow.

A ghazal consists of couplets, each of which is complete within itself, and may not resemble, in thought-content, any other couplet in the ghazal. All the couplets in a ghazal share a common rhyme scheme and meter, but are at liberty to be thematically unrelated. Those who seek the logical development of an idea in a poem, find the fragmentary thought-structure of the Ghazal perplexing; but it is precisely this lack of thematic continuity which is the peculiar virtue of the Ghazal, and which makes the Ghazal a specialized verse-form. Each couplet, holding the complete expression of an idea, is self-contained, and is a poem in itself. Despite its limited space, a couplet is capable of exploring the entire range of human experience, absorbing and describing its complexities. Poetic compression is the distinguishing feature of the Ghazal.

The Arabic word ghazaal' - its derivative beingghazal’ – implies conversing with one’s beloved. Its other etymological meaning is “the painful wail of a wounded deer”. The plaintive note insistently heard in the Ghazal can be ascribed to the state of the lover, who is traditionally presented in the Ghazal as one in anguish. Major poets broadened the scope of the Ghazal and looked beyond the confines of love and wine. They also moved away from the indiscriminate use of conventional or exaggerated and far-fetched imagery and diction. The Ghazal also became a vehicle of philosophical contemplation, and its spectrum included political and social issues.

Ghazals were and are often sung by poets themselves in `mushairas’. In the music world, they were generally sung by courtesans, some of who were renowned musicians. During the early and mid-twentieth century, prominent Ghazal exponents like Zohra Bai and Kamala Jharia, the brilliant young Master Madan, and Begum Akhtar gave a definite shape to Ghazal-singing – what can be called Ghazal-gayaki.

Begum Akhtar laid bare her soul, and the poet’s, in her ghazals. This naked vulnerability made her listeners vulnerable to their own emotional wounds and experiences. One of the reasons for the popularity of Ghazalsinging is the ability to identify oneself with the thoughts, emotions, and situations described, making it meaningful for one.”

In terms of musical lineage, Ghazal is – and should be -the off-spring of Bol-banao Thumri'. (Thumri is of three types -Bandish – ki-Thumri which is composition-oriented; Artha-bhava Thumri' which is sung for Kathak dancers, andBol-banao Thumri’). Bol- banana' means creating musical variations in and around a textual word or phrase. An important element inBol-banana’ is `Kahan’ – the speech intonations within the musical framework – which literally means “manner of speech”.

Earlier, Ghazal was presented in a light-classical concert as one of the allied forms of Thumri. After gaining popularity for itself, it has been plucked out of a light-classical repertoire, and is no longer associated with Thumri. Today, it is seldom heard as part of a larger whole. This in itself is not deplorable, as all art-forms are, mutable with time. The pity lies in improper musical handling, and loss of quality. Even Hindi filmsongs have degenerated, in their quest for commercial success.

Most present-day Ghazal-singers, being unversed with Thumri; have not drawn their musicianship from it, arid are unacquainted with its intensely emotional element of `Pukaar’, which literally means “to call out”; hence their Ghazal-gayaki lacks passion. A Thumri-singer who is well-versed with Urdu, and who comprehends the poetic structure of Ghazal, can render Ghazal ideally ;for a sound Thumri-singer has the necessary Khayal background, and has also been trained to pour passion into a musical renderirig and to evocatively elaborate textual phrases.

Yet even a Thumri-singer’s musical elaboration must be restrained and judicious in Ghazal; if the poetry is swamped with excessive musical treatment, the poetic thread between the two lines of the couplet gets lost. My teacher, Begum Akhtar, once told me that a ghazal is like a painting. The poetry is like the painting itself, and should be given paramount importance, never to be dwarfed or overwhelmed by the musical portrayal, which she likened to an appropriately ornate picture-frame.

Ghazal-gayaki must have covert musicianship. Overt musical technique like sargam' andtihai’ – borrowed Khayal characteristics being popularly used – disturbs the romantic aura of the genre, even while such technique imparts classical seriousness to the Ghazal and dazzles audiences with its inherent virtuosity.

The decline of Urdu as a language, started during Begum Akhtar’s time. ,

She herself, aware of the fact that after the Indian subcontinent’s partition fewer people in India understood the nuances of Urdu, chose to sing along with Ghalib and the other masters – commonplace poetry which had mass-appeal. However, musically she remained true to the Ghazal form. Soon after her death, the void left by her in the Indian Ghazal world, was filled by Pakistan’s Mehdi Hasan, who awed audiences by his command over the classical idiom. He rendered Khayal – oriented rather than Thumri-oriented ghazals in a tender and sentimental manner rather than with the full-throated and passionate style associated with Begum Akhtar. This soft and sentimental style of voice-production became a trend-setting phenomenon. Upon his departure from India, he left in his wake a host of Bombay-based Ghazal-singers, who borrowed his manner, but who were unable to reproduce the musicianship. Also, influenced by Pakistani orchestration; they adopted several accompanying instruments, particularly the guitar.

Because of diluted and tune-oriented Ghazal rendition, they essentially belong to the world of Hindi film-music or `light music’. Their treatment of ghazals as mere songs makes these ghazals musically identifiable with Geet. These tunes, often framing pedestrian poetry, has drawn crowds, and so while the Ghazal has spread from the elite to the masses, it has also degenerated.

Some contemporary Urdu poets are writing forcefully in very simple vocabulary – meeting modern sensibilities. With its changed metaphor, some of this poetry has retained literary quality, even while most commercial Ghazal-singers, select trite, sub-standard poetry for mass appeal.

Audiences often accept what is available to them, for lack of an alternative. Sometimes audiences are musically ignorant, but they can be trained to be discerning and discriminating, simply by being given good fare. Audiences do not create artists – artists create audiences. Excellence of standard and commercial viability need not be mutually exclusive. If artists choose to be unaware of this, and wish to merely entertain, as so many do today, a vicious cycle can set in – as it has between audiences and artists, in terms of deterioration in quality. If facile Ghazal-singers seek justification by saying, “This is what audiences want” why is it that when audiences receive good fare, they gladly accept it, even without complete comprehension? Coleridge has said, ” Poetry is best ~appreciated when half understood”. Perhaps this is true of both poetry and music.

When scientific technology is giving ever-new heights of excellence to audio-cassettes etc. – the medium which takes music to its vastest audiences – should the Ghazal lose its integrity and plummet down?

REKHA SURYA

Deccan Chronicle

Sultans of Sufism

By Debarun Borthakur

Apr 11 2010

Kailash Kher, Sufi singer and member of the band Kailasa, opines “Sufi music doesn’t have a distinctive sound and every time one sings a poem or a creation by any of the Sufi poets, it can be termed as Sufi music with or without any music as the background. So, it doesn’t really matter what genre is backing the poetry. One needn’t have a license to fuse myriad musical styles with Sufi poetry, as it is entirely a matter of individual choice. Jiski jitni budhdhi, woh utna hi kar sakta hai”

Hindustani light-classical singer Rekha Surya who sings Sufi poetry in Thumri-Dadra-Ghazal style informs “Although originally associated with Qawwali in the subcontinent, Sufi music has to do with content rather than form, as it is the poetry which is significant. So one can present Sufi poetry according to one’s musical style. I do think, however, that the music sheathing this poetry should have roots in either classical or folk traditions if it is not sung as Qawwali.

Sufi poetry emanates from Islam but is without heavy religiosity and appeals to people like myself who are not drawn to formal religion. Some Sufi poetry corresponds with ancient Hindu philosophy that allows erotic sculpture on temples. Such mystical poetry is very attractively attired, often wearing the garb of romance. Like two sides of a coin, its interpretation can be either sensual or spiritual. My musical genre, being stylistically romantic, accommodates this poetry with ease.

Compassion for fellow beings is intrinsic in all religions. This commonality transcends religious divisions and is the essence of Sufism, which has caught popular imagination. The popularity of Sufi music is here to stay as it now occupies a distinct space of its own.”

by

REKHA SURYA

North Indian Light Classical Vocal Music

Thumri And Its Allied Forms

Dedicated to

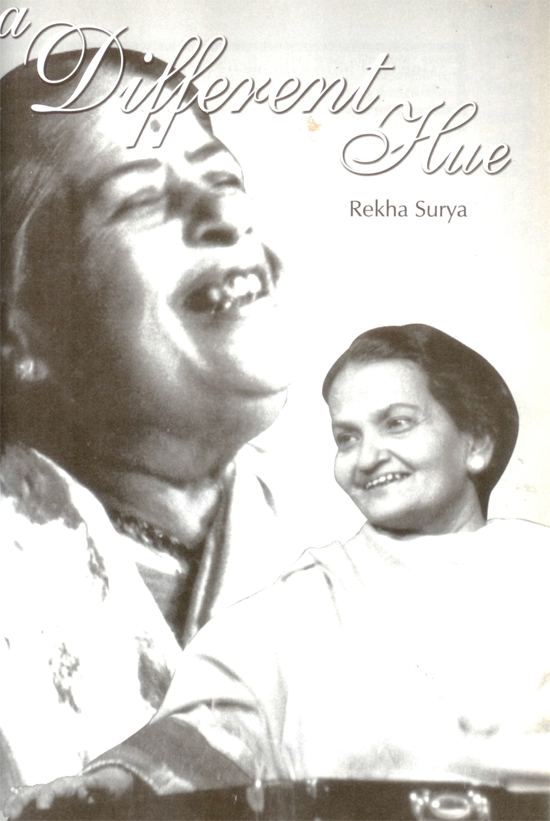

Begum Akhtar and Girija Devi

with gratitude

Epilogue

I was eleven years old when I first attended a Khayal concert in my hometown Lucknow, after which I wanted to learn classical music.

Some years later, I met Begum Akhtar who also lived in Lucknow. A common family friend had arranged a meeting in her home, where I was graciously received but my request to learn from her was flatly refused. She said that bitter experiences with students had made her decide to stop teaching. Just as I was about to leave, she told me to sing something for her. I sang one of her recorded ghazals and she dramatically said “Sirf isliye ke ye aawaaz zaaya na jaaye mein tumhe sikhaongi (I’ll teach you just so this voice doesn’t go waste).”

The next day I started learning from her. Whenever my father fetched me from her house she would tell him, “Allow this girl to sing on stage”. After morning classes she often told me to stay for lunch. In the afternoons we lay chatting on her bed while she stoked the embers of her past.

She told me that sin meant kisi ka dil dukhaana (to hurt someone’s feelings) and added mainey kabhi kisi ka bura nahin chaaha hai (I have never wished anyone ill). She believed that aik achchey fankaar hone ke liye aik achcha insaan hona zaroori hai (to be a good artist it is necessary to be a good person). Once when I had taken a gift for her she immediately telephoned my home to say that though not from her womb I was her child so there was no need for presents. She kept out-of-season fruit for me and began taking me with her for concerts. In Calcutta I saw a man prostrate himself at her feet in adulation. Ammi, as she was called by almost everyone who knew her, died much too soon.

A couple of years later, Girija Devi came to Lucknow to perform. I was invited to hear her sing, accompanied by Shanta Prasad on Tabla, at the home where she was staying. The host told her that my taalim under Begum Akhtar had been cut short. She asked about my plans to continue learning music, offered to teach me and told me to accompany her back to Benares after a few days. So I took the train with her to Benares, where I attended a Chaiti concert—upon entering a maidaan we were served thandai in earthen bowls; on an open stage, several male singers in white dhotis sat cross-legged in a neat semi-circle and began to sing a chaiti, improvising in turns.

Benares had electricity shortage, leading to severe self-pity during riyaaz while sweat trickled down my back. After lessons I was usually sent with a house member on a rickshaw to drink Benarsi lassi. Once Kishan Maharaj came over and invited me to his house where he proudly showed me the varieties of pigeons he reared and portraits of his ancestors, all Tabla-maestros.

I went to Benaras intermittently till Girija Devi accepted the post of Guru at Sangeet Research Academy in Calcutta. I joined SRA for a year, during which it organized a week-long seminar on Thumri—eminent musicologist Thakur Jaidev Singh and others analyzed the genre and excavated its origin. I gleaned facts about Thumri and its allied forms from that seminar and from my gurus, who I have quoted often in my interview while twirling the subject around to view it from all angles.

Icarian against the winds

The flight itself—from Delhi to Kabul—is interesting. Clear visibility allows one to see Lahore below and then the Khyber Pass, once the gateway into the subcontinent for conquerors’ armies. Slowly the terrain changes to brown, barren, bald foothills of the Hindu Kush. Soon we descend to Kabul. I am received by Indian embassy personnel who whisk me away to the India House in a bullet-proof car with the driver and a guardsman both having AK-47 guns on their seats. The car is thoroughly checked at the gate of the embassy, which is situated close to the US embassy and NATO’s air-base. I wonder about the intent scrutiny as we are non-suspect Indians but I’m told that a “magnet bomb” may have been picked up by the car along the way.

As I settle into my room, I hear the sound of disturbingly low-flying helicopters overhead. I think they are probably being used for surveillance but no: NATO and some other US agencies commute by choppers for security reasons. My predominant memory of Kabul is this sound which sometimes made the house shudder. Things are so secretive that even I am informed only upon arrival where my concert is being held. The audience has been invited just two days back. The venue is RTA—Radio and Television of Afghanistan. The concert is a belated celebration of India’s and Afghanistan’s Independence Days, the dates being close to each other. The hall is full on the day of the concert; Afghans are known for their love of Indian classical music. The audience is responsive and sophisticated.

A muddy history

Next day, I am surprised to find a few newspapers articles ranting against Pakistan. I ask my host, ambassador Amar Sinha, “How is it that Afghans seem as upset with Pakistan as we are?” He replies, “Even more so than us”. After a few dinner conversations, I learn the Afghan Taliban, which came in the wake of the US-backed mujahideen who fought Russian occupation during the Cold War, disbanded in 2001; the Taliban that now creates mayhem operates out of Pakistan, whose covert plan to expand into Afghanistan is a pursuit of parity with India in terms of size. Battered by war, a weakened and vulnerable Afghanistan is easy prey for Pakistan, whose Taliban combats the elected Afghan government and seeks a return to Sharia law. Of course, they are also useful as freelance terrorists elsewhere. For the Taliban, it’s all about territorial gain.

I have a blast in Kabul, but the fear of blasts of another kind means I am limited to a visit to the magnificent Bagh-e-Babar where Babar was buried and later to the Parliament House, being constructed by India diametrically opposite the Dar-ul-Aman—the hauntingly beautiful palace of the Afghan kings, still grand with its tall columns—but damaged by bombing. The two monuments confront each other with inexorable beauty.

En route to Herat

Recently I accepted an invitation to sing Sufi poetry for a conference in the ancient city of Herat, once the cultural centre of Afghanistan. Its architecture is comparable to the better known Silk Route cities of Esfahan and Samarkand in neighbouring Iran and Uzbekistan. The Silk Route sprang to life in the 1st century BC, stretching across Central Asia to the Mediterranean; it was not a single highway but was a network of trade centres. Caravans with several hundred camels laden with merchandise made their way between China and Persia via Herat. Medieval urban layouts in this region had three sections—a bazaar, a mosque and a fort. Kabul, Kandahar and Herat earlier had renowned bazaars but only Herat’s medieval bazaar survives. It is one part of the Old City and has retained its original street plan. The famed Afghan carpet emerges from Herat. Some modern-design carpets have the image of Ahmed Shah Massoud, the mujahideen fighter—a national hero. The other two parts of the Old City are the Friday mosque and the citadel. The Friday mosque stuns with exquisite mosaic tiles.

The Herat citadel stands on the foundations of a fort built by Alexander the Great and is the venue of the two-day global conference on Islamic extremism which included participants from Europe and the USA. It began with the observation that while Europe in the Dark Ages was mired in ignorance, the significant achievements of Islamic scholars in medieval times makes it all the more inexplicable that strands of Islam have turned to a reductionist, violent credo. The conference ended with my Sufi concert, after which the organisers made the announcement: “After forty years a woman has sung publicly in Afghanistan—last month in Kabul and now in Herat.”

Last Week

Dupree’s Afghanistan tells me that the Mauryans went into Afghanistan during 4th and 3rd centuries BC, followed bythe Guptas in the 4th century AD.

A practitioner of the Lucknow and Benaras gharanas, Delhi-based singer Rekha Surya is the author of Sung in a Sensual Style; E-mail your diarist: rekha_surya [AT] hotmail [DOT] com

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nulla vel turpis id ligula placerat varius. Cras sodales facilisis faucibus. Morbi malesuada turpis eget finibus varius. Integer eget ullamcorper ipsum, sodales dignissim felis. Cras facilisis eros at turpis gravida, non feugiat metus finibus. Duis nec libero volutpat, fringilla massa a, venenatis nunc. Morbi id feugiat enim. Proin posuere luctus pellentesque. Praesent accumsan augue lectus, vitae posuere est vehicula nec. Suspendisse porttitor ut est non ullamcorper. Vestibulum pretium metus libero, vitae mollis lectus luctus ut. Maecenas nec ex sapien. Duis bibendum orci in tellus eleifend pulvinar. Sed ornare aliquam ligula vitae tincidunt.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nulla vel turpis id ligula placerat varius. Cras sodales facilisis faucibus. Morbi malesuada turpis eget finibus varius. Integer eget ullamcorper ipsum, sodales dignissim felis. Cras facilisis eros at turpis gravida, non feugiat metus finibus. Duis nec libero volutpat, fringilla massa a, venenatis nunc. Morbi id feugiat enim. Proin posuere luctus pellentesque. Praesent accumsan augue lectus, vitae posuere est vehicula nec. Suspendisse porttitor ut est non ullamcorper. Vestibulum pretium metus libero, vitae mollis lectus luctus ut. Maecenas nec ex sapien. Duis bibendum orci in tellus eleifend pulvinar. Sed ornare aliquam ligula vitae tincidunt.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nulla vel turpis id ligula placerat varius. Cras sodales facilisis faucibus. Morbi malesuada turpis eget finibus varius. Integer eget ullamcorper ipsum, sodales dignissim felis. Cras facilisis eros at turpis gravida, non feugiat metus finibus. Duis nec libero volutpat, fringilla massa a, venenatis nunc. Morbi id feugiat enim. Proin posuere luctus pellentesque. Praesent accumsan augue lectus, vitae posuere est vehicula nec. Suspendisse porttitor ut est non ullamcorper. Vestibulum pretium metus libero, vitae mollis lectus luctus ut. Maecenas nec ex sapien. Duis bibendum orci in tellus eleifend pulvinar. Sed ornare aliquam ligula vitae tincidunt.